It takes about eight hours by speedboat from Cartagena del Chairá’s town centre to reach the village of El Guamo in the lower reaches of the Caguán river. Those who have made the trip before are aware that the fare is 170,000 COP, a high figure for other latitudes but natural in this region of the country with few state regulations.

They have become accustomed to surviving in the Caqueteño jungle, which is part of the Amazonian ecosystem, without the full presence of the state and clinging to any economic activity that can sustain them. However, the desire to achieve this stability has an impact on the environment. The region’s peasant leaders are aware of this.

“We know that what we’re doing to the jungle is grave, we’re not so stupid, we understand,” says a peasant farmer deep in the mangroves of Bajo Caguán who prefers to remain anonymous for security reasons.

This farmer questions the efforts made by some of the state officials to conserve the environment and support communities in these tasks. “They come and say: ‘in the boat comes a 1,000-litre container to store water’, and then you are happy because if you don’t have enough money to buy it, you let yourself get tangled up and nothing else comes”. And another farmer adds: “the whole government is like that: they see that there are poor peasants here, ‘they have nowhere to drop dead, let’s get them involved’. And we receive what they offer because we need it.”

The tragedy facing the communities of Cartagena del Chairá today is not the war. What really has hundreds of Chairences under siege, and with them the Amazon rainforest, is the lack of titles to the lands they inhabit and their dependence on an economy that is unviable with the Amazon, such as extensive cattle farming, which becomes a replacement for their dependence, in the past, on the illicit economy of growing coca leaf for illicit use.

“To be honest, all of these nuances arose in the territory as a result of a lack of opportunities. There hasn’t been much recognition of the need for these peasant communities to have other options for life and production”, Aristides Oime, a social leader in the municipality, says.

Leoncio Montaña Bahamón, a farmer from the village of Las Quillas, is the voice of this lack of opportunities: “You plant a crop, for example, plantain, cassava or something like that, but it’s for your own consumption because there are no companies or anything like that will buy the goods… Nothing. If one goes to Remolino (del Caguán) with a bunch of plantains, it will be at a loss, so then what are you going to grow crops for? Because transport is very expensive, and when one arrives at the top (to the municipal capital) the food, such as plantains, arrives in a bad state”.

There are numerous conflicts between peasant needs and the environment, and hundreds of families in the municipality are requesting that they not be singled out without first learning about their shortcomings. One such example is the community of Las Quillas, which is made up of 18 poor families, the majority of whom do not have titles to the land they live on and rely on small-scale logging to supplement their cattle farming income.

With the assistance of the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), these families were able to obtain resources in 2018 to construct a 300-metre wooden bridge from the Caguán River to their farms. However, due to the humidity of the jungle, they have to cut down trees every year to rebuild the damaged parts of the bridge, increasing the number of forests cut down out of sheer necessity.

From words to actions

Faced with the difficult Amazonian soil, the armed conflict, the place that extensive cattle ranching has taken in the region, and the cultivation of illicit crops, some peasant families have taken action to try to stop deforestation and turn around their socioeconomic conditions, thus advancing in the strengthening of ecological awareness that is beneficial to the Amazonian ecosystem.

Previous experiences have demonstrated that it is possible to find alternatives for the sustainability of Caguán’s communities without destroying the forests. This was the intention of Giacinto Franzoi, known in the communities as “Father Jacinto”, who came to Remolino del Caguán at the end of the 1980s to propose to the peasants to replace coca leaf crops for illicit use with cocoa plantations and export chocolate under the name “Chocaguán.”

Several projects in the region are being promoted in order to reduce extensive cattle farming, as was once the case with coca leaf. Baudilio Endo, 58, is one such story. He arrived in Bajo Caguán 38 years ago. This farmer’s story is similar to that of the majority of Cartagena del Chairá’s peasants: he arrived in the municipality in the 1980s, following the trail of the coca leaf and the illusion of obtaining a plot of land. After experiencing the stress of being dependent on an illegal business, he decided to venture into livestock farming in 2010.

Endo is one of a group of Chairenses who own the land on which they work. The agrarian authority granted him ownership of La Reforma, a 53-hectare farm in the Amazon Forest Reserve, just a few meters from the start of this Area of Special Environmental Interest. But, with the wisdom of years and experience, as well as the loss of his desire to make money at any cost, he criticizes the municipality’s landowners and proposes solutions.

“For example, the open lot that a single 600-hectare area has, which you can find around here and in which six families can be in, being well off with small farms and with cattle with good genetics,” says Endo.

Because Endo has title to the land on which he lives and works, he has been able to benefit from forest conservation projects, which is why he has not deforested to any significant extent for nearly ten years, keeping 23 hectares of the entire property in forest. He has cleared half a hectare for food production in some years, but he has also been quick to reforest with abarco, aguarrás, yellow oak, or sevillana trees.

Yamit Cardona is another example. He arrived in Remolino del Caguán at the age of four, which is why he considers himself to be another Chairense. The FARC guerrillas kidnapped his father and brother, but he never left the Caguán region. He started scraping coca leaves and living like a raspachin (coca collector) when he was 14 years old. Years later, he turned his life around and has spent the last seven years working as a teacher in the village of Buena Vista.

The Buena Vista school proposed planting 500 trees through the School Environmental Projects (PRAE), an initiative that incorporates critical local environmental situations into various activities of educational institutions.

“If I start with a child at a very young age and tell them: ‘see, we are going to plant this, explain to them that if we plant a fruit tree it can give us fruit in the future, if we plant timber trees too, if we plant shade trees too, but the same thing happens as with the State: the PRAE just says do, go and work there… Send us tools, send us material, support us, but in the end, they leave us alone,” the teacher explains.

Another issue that stands out is the lack of continuity. Rural teachers sign contracts with the Ministry of Education, which determines which village and department they will work in. Thus, projects like the tree-planting project that Cardona is carrying out are dismantled, as it happened at a school in the neighbouring village of Monserrate, where a teacher had planted 200 trees with his students, but then he was changed at the beginning of this year, and the person who replaced him had no idea what was going on.

Just like Cardona and Endo, hundreds of families have taken an interest in living in harmony with the Amazon rainforest. Little by little, they are consolidating their ecological awareness.

The “model farm”

The peasants of Bajo Caguán are eager for public and private institutions to stop pursuing isolated projects and instead collaborate to ensure that what they propose for forest conservation and the improvement of their socioeconomic conditions yields tangible results.

“They come here, gather two or three communities, talk nicely, and tell us that they are going to help us. You think to yourself, ‘maybe this one will,’ and then another one comes along who talks even better, and that’s where we are. And these middlemen keep the money “, according to a peasant farmer who was interviewed.

While the farmers of Cartagena del Chairá continue to wait for the government to provide them with comprehensive solutions for living in the Amazon without negatively impacting it and the opportunity to grow their peasant economies, some have begun to take environmental conservation into their own hands.

“We’ve already adapted to our new surroundings. We want the area to be respected and for people to live peacefully here. We’ve started our families. Most of us were born in other parts of the country, but I feel like I’m from here, and I believe many others do as well”, according to Rafael Rodrguez, former president of El Guamo’s Community Action Board. Families must change their relationship with the jungle in order to live peacefully in the Caguán region.

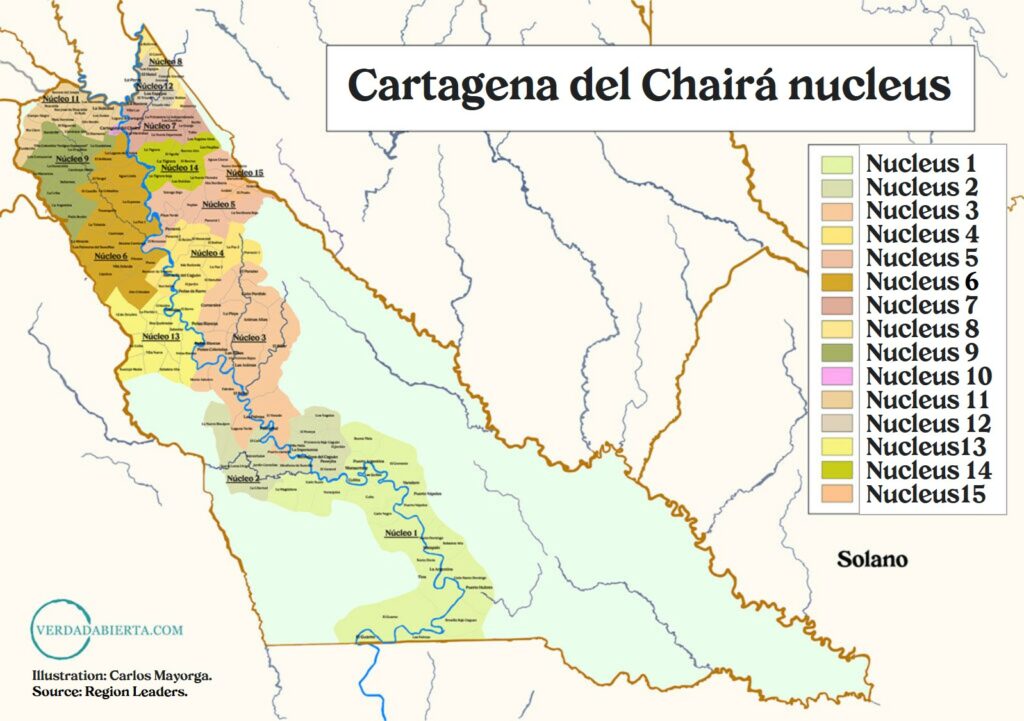

One such case is sprouting in the municipality’s lower part, thanks to the community-based integral farmer’s association, Nucleus 1, in Cartagena del Chairá (ACAICONUCACHA). The Cartagena del Chairá communities have a strong and truly unique organizational process. During the years of control by the 14th Front of the former FARC in the mid-1980s, the leaders consolidated their leadership, agreed to group the municipality’s hamlets into “nuclei,” and established coexistence manuals that included, among other things, environmental care.

Since 2020, ACAICONUCACHA has collaborated with the Sinchi Institute on a development plan in which 16 villages and at least 600 associates want to bet on the concept of the “model farm”: land to be worked in a technologically advanced and sustainable manner, where they grow crops and some products for the market whilst having a few cows and other animals and, also, reforest by planting native trees.

“Sinchi was extremely helpful in obtaining legal status for the association and the model farm project. We looked for resources, and some people have already given us some rolls of wire and a battery for implementing energy for the fences and house lights”, according to the former president of the Community Action Board of El Guamo.

The installation of a processing plant for the fruit of the Canangucha or Moriche palm, an Amazonian species cultivated in the Caqueta region, from which various products for human and animal food can be extracted, was part of the project’s implementation. Despite the fact that it was completed, it is not operational. This news portal discovered that in fact, the processing plant was closed in the village of El Guamo, with the machinery covered in dust.

According to the community, the SINCHI Institute never handed over the facilities with the final adjustments, and there was no assistance to continue with the project in the production phase. Officials from this institution arrived at the site at the end of April this year, promising that they would bring the community together and put the plant into operation the following June.

Although the productive projects in Bajo Caguán are not yet a reality, belief in the model farm concept remains strong. Hector Agudelo, a 65-year-old farmer who has lived in the village of Las Quillas for the past 35 years, is one of those who wants to change the way communities interact with the Amazon rainforest.

“I have a farm… “, says the farmer, “… But I don’t count on it because it’s located in the Forest Reserve Zone, and they won’t give us titles for that; adding to that the fact that they don’t want us to cut it down to plant grass for the cattle, but we want to continue working… I’m old now, I’m ready to die, but I have a very young son and I want to leave him off well. The only alternative we have is the subject of the new farm, the model farm as they call it: to sow cut grass and plant yucca and bananas in the little area we have that’s been deforested.”

The Cartagena del Chairá Municipal Agro-environmental Roundtable for the Right to Land has developed a proposal for a “model farm” for the region’s reality. “This is dependent on the state’s and the government’s willingness to invest in the region. We have stated that ‘if the government is willing, we will stop deforestation’”, says Aristides Oime, Roundtable member and regional leader.

Given the slowness of the state, non-governmental organizations such as the Foundation for Conservation and Sustainable Development have played an important role in accompanying the peasants (FCDS).

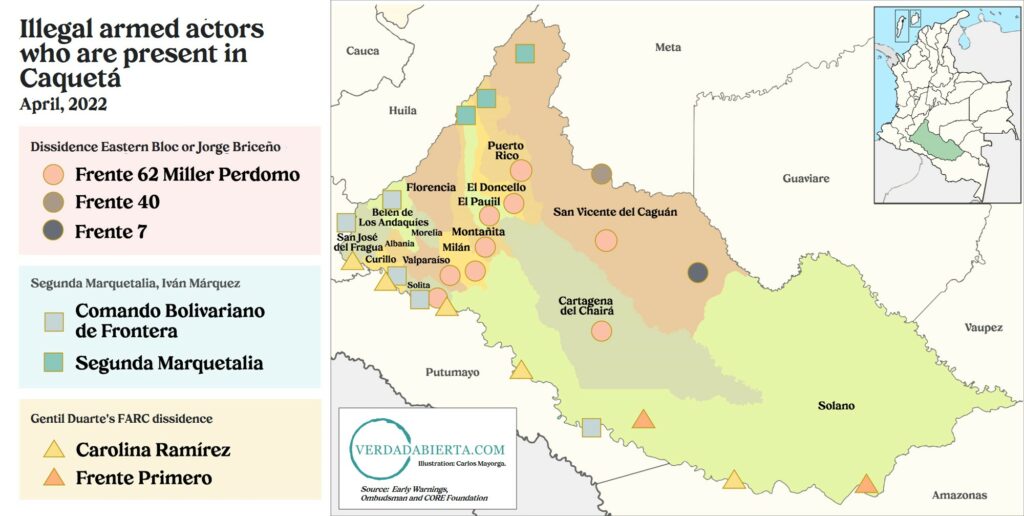

“Because several have arrived, but the manner in which they have done so, or the permanence, has not been the same, there have been very few options in which organizations or the state have offered projects. What we’ve accomplished allows us to move with a sense of calm”, says Emilio Rodríguez, a researcher at the FCDS, noting that the armed conflict means they must be cautious in the region to avoid problems with dissidents of the now-defunct FARC guerrilla due to the strict control they exercise over outsiders visiting the Caguán region.

“There is a great opportunity to do an agroforestry project, which means that where there was previously a pasture, a system of timber trees, fruit trees, and pancoger (crops that are corn, beans, cassava, and bananas, among others) should be planted. And both the fruit trees and the pancoger will be useful to their domestic economy in a short period of time”, explains Rodriguez, which translates into helping families’ economies by reducing their reliance on store-bought fruits and vegetables, reforesting affected areas, and developing a peasant project that generates income for families.

With these goals in mind, the FCDS is demonstrating to the communities how community forestry can help them develop, in part, what they have dubbed the “model farm”. Ninety families in Nucleus 1 have joined this proposal and are investigating the possibility of harvesting timber and non-timber products with Sinchi.

“A lady in the village of El Capricho gave us tomato tree juice; imagine where that tomato tree grew! The tomato tree grows above 2,000 meters above sea level. That lady paid for that tree tomato to give us juice, ignoring the fact that she’s surrounded by a forest where she could have a lot of Caguán forest products and fruits from which she and her family could benefit “, explains Rodríguez.

Some of the most profitable products in Bajo Caguán are azai or melipolicultivation, from which honey can be extracted at a high market price, which is why approximately 20 families will begin producing honey with the Foundation.

Given the difficult soil for agriculture and the high costs of transporting the products upriver, how profitable is it to promote azaí and beekeeping projects in Bajo Caguán? Hundreds of farmers in the area have asked this question: “Who buys these products, I wonder? Where is the project being sold? We plant a quarter-hectare of arazá, which produces a lot of fruit, and after we load the harvest into the boat to take it out, do we leave that seed to rot? There is no sure-fire way out “, claims a farmer from Las Quillas.

The expert’s response to the aforementioned is that for this type of project to be successful, it must be designed specifically for a specific market. “If you produce honey from bees in Bajo Caguán, it is associated with the protection of the forest that borders and protects Chiribiquete, and it must be sold in a different way and to a different target public. I am confident that there will be people interested in purchasing this type of product, even from outside the country”, he says without a shadow of a doubt.

In this respect, Rafael Rodríguez, from his farm in the depths of Bajo Caguán, considers that this type of proposal is a good alternative for peasants like him, who have deforested between 30 and 40 hectares, to stop cutting down trees and begin to recover the forests.

“We are looking for a way of life in the region that we can sustain ourselves…,” says the former president of El Guamo’s Community Action Board, “… And we believe that with new styles of farms we can do it, but the problem is the floating people in the region. Some of us accept this responsibility, while others do not, making it difficult to reach a general agreement, and I’m not just talking about El Guamo, but about the Caguán river in general.”

“We need Payments for Environmental Services,” says this farmer, implying that the state should give money to families in exchange for conserving the forests on their land. However, in order to access these conservation incentives, the land tenure situation of the Chairenses must be reviewed jointly with the state, as the Oime leader demands: “go and check because there are many farmers who may not have the document, but have a tradition of years in the territory.”

Natural Conservation Contracts are expected

“To achieve zero deforestation, institutions or the state would step in and say, ‘we are going to contribute a monthly payment to each farmer so that they don’t cut down their forest, only just for food’, so, both myself and the community are here, waiting for that day to arrive”, says a farmer from the village of Las Quillas.

Until now, the Natural Conservation Contracts have been the only option on the table for families like the ones from Las Quillas’ who live and work in the Forest Reserve Zone to ensure their permanence in the territory and receive income for caring for the forest (CCN).

This is a comprehensive conservation strategy that, for the first time in Colombia, allows for the legalization of peasant communities’ historical occupation and the promotion of sustainable management in Areas of Special Environmental Interest designated by Law 2 of 1959, the replacement of illicit crops, and the strengthening of communities’ agricultural production in specific polygons determined by the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development.

This pact would provide some legal security to the families who subscribe to these CCNs by allowing them to be a recognized occupant for a period ranging from 1 to 10 years, depending on the activities they carry out, with the possibility of extension if their contractual obligations were met.

“According to article 7th of the Climate Action Law No. 2169 of 2021, CCN is a strategy that includes the granting of Land Use Rights and the conclusion of Conservation Agreements with rural families who inhabit unallowable wastelands, such as the Forest Reserve Zones of Law 2a of 1959”, writes Tatiana Watson, manager of the Presidential Council for Stabilisation and Consolidation, in a written response to this website.

What exactly are these two components? According to the manager of the Presidential Council for Stabilisation and Consolidation, Voluntary Conservation Agreements are mechanisms that guide land management, provide access to payment for environmental services, develop restoration processes, and/or establish long-term productive projects.

Conservation Agreements can only be delivered after Right of Use Contracts are granted, a legal act granted by the National Land Agency (ANT) that grants “the right to the use and enjoyment of the land, recognizing the environmental regulations, including the Forest Reserve established by Law 2 of 1959.”

However, the demand for Right of Use Contracts became a source of contention among Cartagena del Chairá’s former coca-growing communities. According to the peasants, the User Agreements do not guarantee land ownership and create insecurity for the lands of the inhabitants because they do not recognize their official ownership.

The signing of the Peace Accord accelerated the transition of Cartagena del Chairá’s economy from coca to livestock, but it could have been different if the families who planted the illicit crop had other agro-productive and sustainable state projects.

“It was the right time for the state to come to the territories to provide farmers with alternatives for technification or for livestock or agricultural training in the region, with productive projects, not with minor projects of ‘we’ll give you 20 hens; two, three pigs; and that’s it'”, says Aristides Oime.

This leader and dozens of peasants with whom this portal was able to speak are referring to the implementation of the National Programme for the Integral Substitution of Illicitly Used Crops (PNIS), through which productive projects would be consolidated to remove 2,347 families (1,548 growers, 56 non-growers and 743 collectors) from coca leaf cultivation in this Caqueteño municipality.

However, after several years of waiting for its effective implementation, they now feel disappointed and confused. (Read more in: PNIS, a programme that has been implemented in dribs and drabs).

Although monitoring reports on the implementation of the Immediate Attention Plan issued by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) show that by 2020, more than 70% of the country’s food security assistance had been achieved, the process was marked by serious non-compliance and productive projects stalled, in part because many families who signed this agreement and voluntarily eradicated live in Forest Reserve Areas, hampered implementation.

The alternative proposed to develop the PNIS in these Special Environmental Protection Areas was through Natural Conservation Contracts, but the terms for accessing these did not go down well with the communities.

“Why would they take two million pesos out of the PNIS to assume the commitment of the Right of Use contracts?” asks an annoyed farmer from Las Quillas.

According to several farmers, PNIS officials met with them to inform them that if they wanted the productive projects to be developed on land within the Amazon Forest Reserve Zone, the program would “discount” two million pesos from the amount that each family had set aside for the productive projects, money that would be used to carry out the ANT’s requested inspection of the land.

Watson of the Presidential Advisory Office for Stabilisation and Consolidation clarifies that neither of the two components of the Nature Conservation Contracts – Use Rights Contracts and Voluntary Conservation Agreements – are free of charge to stakeholders.

“The procedure to advance the CDU -Contracts of Rights of Use- has no cost for the families. The technical studies imply some costs that the agricultural sector leads with the support of allies such as public, private or international cooperation entities, but in none of the cases is the cost assumed by the family”, explains the official.

It specifies that “the value of such studies will be determined according to the conditions of the study areas” and, similarly, assures that “the Voluntary Conservation Agreement, in Payment for Environmental Services schemes, has no cost for the entry of beneficiaries”.

VerdadAbierta.com contacted the press office of the National Land Agency (ANT), in addition to emailing Campo Elías Vega Rocha, deputy director of Land Administration of the Nation, to find out about the alleged costs that families were being charged for the PNIS funds for the studies of the Use Rights Contracts, but at the time of going to press no response had been received.

In an interview with this portal, Hernando Londoño, director of Illicit Crop Substitution at the Agency for the Renewal of the Territory (ART), clarified that no money was being taken from the seven thousand families living in the Forest Reserve Zone and no money was being deducted from the PNIS.

“The investment of public resources in public property in favour of private individuals is not only prevarication by action, but also embezzlement in favour of third parties. I cannot invest public resources in territories owned by the nation in favour of private parties”, Londoño said.

“The Forest Reserve Zones,” he adds, “are property of the Nation, public goods, and the PNIS resources are public goods, only that they go to a third party that said it was going to replace them, but that third party is located in the Forest Reserve Zone. I cannot implement productive projects for a peasant farmer if he does not have the right to use that territory.”

“This is a problem between a beneficiary (of the PNIS) and the National Land Agency… “, he continues, “… It is not my problem. The only thing I have to say to the farmer is ‘show me the right of use that the Land Agency gave you in order to implement the PNIS, but if I act under that strict order of what I am saying, then I will never implement the PNIS’.

The ANT replied to Londoño that it had neither the money nor the people to do this. For this reason, the PNIS director proposed to Campo Elías Vega that, through the operators of the Programme for the Substitution of Illicit Crops, he could carry out the inspection of the properties, so that the ANT could carry out the administrative procedures with the information gathered in the territory.

In the Polygons set up by the Ministry of the Environment in the Areas of Special Environmental Interest, Londoño spoke to the families to tell them that the PNIS directorate was going to help them obtain the Use Rights Contracts, including several families from Cartagena del Chairá.

“What did we do as a Programme? Come on, Mr. farmer, we help you with the Right of Use and your processing costs are assumed by the Programme, and we ‘give’ you seven million from the short-cycle projects – because there are nine million in total – until I receive resources to cover the two million that the processing of the Right of Use costs me”.

What Hernando Londoño told VerdadAbierta.com is that once it has sufficient resources, the Directorate for the Substitution of Illicit Crops will complete the two million for the short cycle that will be taken from the PNIS resources with money from another fund that he did not specify, with the families from all over the country who expressed their desire to take this alternative up to 18 April.

“Here they are trying to tell people: ‘this is how it is and you either sign it or you don’t’,” questions Rodríguez of the FCDS, who believes that special care should be taken to ensure that this is an exercise in dialogue in sight cannot be lost of the fact that they are trying to grant vulnerable communities the right to use land in protected areas under conservation parameters.

Priceless opportunity stalled

The FCDS researcher considers the Natural Conservation Contracts to be a great opportunity to halt the decline of the Amazon: “This is where a good part of the solutions begin, because it is there that the state makes a first recognition of a farmer who is settled in the Forest Reserve of Law 2, be it zone A, zone B, zone C; this did not exist”.

“What happens is…” he continues, “… That putting it into practice is complicated, and in my opinion, because a large part of this exercise is associated with those who have been growing coca, but there is a lot more potential for families who are no longer involved, but I do believe that there’s a lack of education on the subject.”

However, the Chairenses have little to regret, as the implementation of the Nature Conservation Contracts has not achieved the progress that had been announced in the face of the great expectation it generated among the communities.

Andrés Valencia, current president of the Board of Las Quillas village, explains that in the region they have held community meetings to discuss opportunities for payments for environmental services: “we are for that, we are committed to no cutting down, that the mountain we have gives us the sustenance to sustain ourselves and to work with the cut pieces we already have… “, he says, “… But for that the families in his community need Conservation Contracts.”

On February 17th, 2021, the same day that vaccination against Covid-19 began in the country, President Duque’s government announced the start of another important process: the delivery of 111 Natural Conservation Contracts to families in the municipality of Tierralta, Córdoba, where hundreds of farmers will receive payments for environmental services for conserving 400 hectares of forest.

On that day he announced that the government’s goal would be to deliver 9,596 Nature Conservation Contracts by the end of his term in 2022. In 2021 alone, he had set a target of delivering more than 5,000 of these; however, with four months to go before the end of his term in office, the results would show a resounding failure on those claims.

According to the Presidential Council for Stabilization and Consolidation, only 111 Tierralta contracts have been delivered to date, with 200 Right of Use Contracts signed. “The remaining processes are in the execution stage”, they say, adding that while there are no contracts of this type in Caquetá, there are 649 processes in the department aiming to sign Right of Use Contracts: 345 in San Vicente del Caguán, 181 in Cartagena del Chairá, 49 in Solano, 35 in El Doncello, and 30 in La Montanita.

The communities that VerdadAbierta.com was able to talk to in Cartagena del Chairá were interested in signing the Natural Conservation Contracts but were concerned that they were uncertain about what would happen to their permanence in the territory after the term of these contracts expired.

In this regard, Watson tells this portal that the minutes of the contract establish the option to have extensions and the possibility of continuing to occupy the property properly even if the contract is terminated. In case of early termination of the contract by mutual agreement, “the AGENCY will resume the administration of the BALDÍO PROPERTY according to its functional and missionary competencies, without this meaning the delivery of the same by the USER”, specifies one of the clauses.

Hundreds of families have great expectations, although they are still only dreams: “If someone were to arrive… ” says a farmer from the region, “… And tell us ‘this is for you and every month, every two months, every six months, every year we are going to pay you so much to conserve’… but that someone would arrive at least! Here, entities keep arriving and nothing happens.”