Because the rainfall in the Colombian Amazon decreases between November and February each year, the levels of tree felling and burning rise during these months. Traces of this practice can be found along the road that connects the municipalities of El Paujil and Cartagena del Chairá in Caquetá.

The burnt pieces of yarumo and ceiba lying on the ashy grass and orange soil, on the other hand, are far from the main cause of deforestation in the Amazon. These are the small burns left by families who deforest in order to survive in the only way they know how: by encroaching on the forest.

“The peasant is not the most prolific deforester. People arrive with a landowner’s approach, in addition to the rules of coexistence that we have. When a peasant farmer is not trained to cut down 100, 200, or 300 hectares, these people do it”, according to a peasant leader from Cartagena del Chairá who prefers to remain anonymous for security reasons.

Higher levels of deforestation can be seen in the Caguán River’s waters. Hundreds of cattle are transported by barge to the municipal capital of Cartagena del Chairá to be sold.

People from outside the region who arrive in Caguán are looking for profits from extensive cattle ranching at the expense of the jungle in a municipality where communities are eager to get their hands on a piece of land and where the cattle business is presented as the best legal way to make money.

Poor peasants who cut down two or three hectares a year to grow food crops and keep a few cows; landowners who hire impoverished peasants to cut down large tracts of forest and manage their cattle; and peasants with land who collaborate with ranchers to consolidate cattle ranching and ambitiously expand their pastures to the detriment of the jungle are the three groups involved in deforestation practices in Cartagena del Chairá.

How did the forest disappear in Cartagena del Chairá, a territory only a few could enter? Everything seems to indicate that not even war can stop the cattle plan that is destroying the Amazon; in the meantime, the state wrongfully persecutes the most vulnerable populations, which it never cared for in the first place and now criminalizes.

FARC out, deforestation in

A leader who has lived in Caquetá for more than a half-century and in the Bajo Caguán region for nearly four decades, he worked as a teacher in the department in the 1980s until resigning to pursue a lucrative business in Cartagena del Chairá: the cultivation of coca leaf for illicit use. He became involved in the organizational process over time, became a community leader, and helped to establish several Community Action Boards (Community Action Boards).

Back then, the jungle was cleared to expand the coca leaf plantations, but deforestation was not a major concern. Chainsaws had not yet been introduced in that decade, so trees were cut down with an axe, mostly for plots of half a hectare, according to some leaders.

“I am someone who actively participates in the processes, and the government in this region has never sent anyone to instruct, socialize, or teach us. We peasants have continued to work these lands through environmental culture: slash and burn, burn and sow. Of course, we had no idea we were harming the environment… we had no idea” This leader, who prefers to remain anonymous, expresses himself with a hint of guilt.

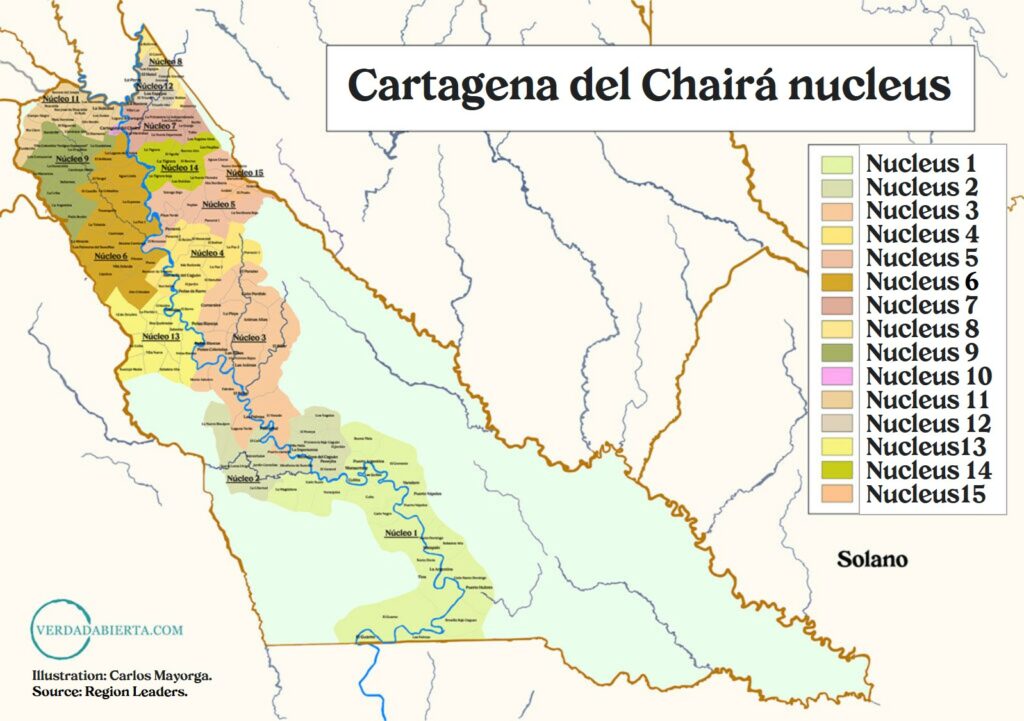

For years, it was the former FARC guerrillas, particularly the 14th Front, who imposed environmental care in Caguán, encouraging and respecting leadership and organizational processes in the region. As a result, the communities of Cartagena del Chairá agreed to organize the municipality’s villages into “nuclei” and form committees to ensure coexistence and environmental stewardship. Murcia is the Nucleus 4 coordinator.

“They – the former FARC – taught us through the Environmental and Agrarian Committees that we had to protect the flora, fauna, and water sources; this is documented in our coexistence manuals, as well as that nothing can be cut down within 30 meters of a riverbank or within 30 meters of a water source; tapirs, deer, tigers, or curassows cannot be killed also. Anyone who does so is fined up to five million pesos by the village committee”, the leader reminds us.

These coexistence manuals to which the leader refers became the tacit laws of Cartagena del Chairá from the mid-1980s onwards. The rules established that a settler, in order to clear forest, had to ask permission from the Community Action Board, the Agrarian Committee and the Environmental Committee, which established how many hectares he could deforest and always in small plots. Through these agreements, the former FARC supported social processes and ensured the care of the forest.

These manuals state that “there will be no more colonisation in protected areas,” that “no farm should be left with less than 25% of mountain reserve,” and that the Community Action Boards should keep a census of the farms, specifying the hectares of pasture and virgin forest in each of them; it is also requested that outsiders entering the region notify the region’s leaders. However, since the signing of the Peace Accord in November 2016, these instructions have not been followed as strictly as they were during the former FARC’s rule.

With the departure of this guerrilla group on their way to reincorporation, the peasant communities of Cartagena del Chairá were left without a state and without law, but with the commitment to care for the jungle as they had done in the past; however, the outsiders who began to arrive ignored such agreements and are shamelessly attacking the environment.

Several municipal leaders recall that in September 2016, they received reports from some villages that “new people” had entered to invade forest reserved areas, specifically in three villages: Lejanas Uno, Lejanas Dos, and Monterrey, all of which are part of Nucleus 7.

The leaders immediately filed a complaint with Corpoamazona, the region’s environmental authority, using the minutes submitted by the Community Action Boards, warning of what would be the start of an avalanche of tombs and burnings, but they put it on hold.

On December 13th, that year, one of the leaders was summoned to present the deforestation picture to various state institutions in charge of environmental protection. He drew a map and pointed out the three villages where, according to the Community Action Board records, 42 people had initially entered, but three months later, at least 880 people were known to have taken virgin lands in the Amazon Forest Reserve Zone.

In the months that followed, the “environmental bubble,” an inter-institutional articulative initiative led by the Sixth Division of the National Army, began to be implemented in Caquetá in order to prevent, intervene, and mitigate deforestation – a model that would later be adopted in the departments of Amazonas, Guaina, Guaviare, Meta, Norte de Santander, Putumayo, and Vaupés. However, the outcome of said initiative has not been as anticipated.

But who were these people who had arrived to take over areas of the virgin forest? Many came from municipalities such as San Vicente del Caguán, Puerto Rico, and El Paujil, according to the communities. “Some rich people financed them to go and take 500 hectares of mountain and gave them 15, 20 million pesos,” explains a municipality leader who requested anonymity for security reasons.

Some of these forest occupations had begun years before but without the massive deforestation footprint. Tierra Linda, a hamlet that grew dramatically in 2017, is one of the most notorious cases in the region. According to regional leaders, in 2010, 23 families presented themselves before the Community Action Boards of Nucleus 2 with a supposedly signed permit to settle in Cartagena del Chairá signed by the former FARC – but not by the 14th Front that operated in Cartagena del Chairá, but by the Teófilo Forero Mobile Column and the Eastern Block.

This is how each family acquired between 117 and 500 hectares of virgin forest on a plot of land seven hours by horseback from Remolinos del Caguán to the vicinity of the La Urella stream, and a few kilometres from the Serrana de Chiribiquete National Natural Park. Following the FARC’s departure at the end of 2016, families cleared large swaths of mangrove forest.

Although the leaders of Cartagena del Chairá did not agree with the situation, they could not oppose the alleged permission they had received from the former FARC. However, there are rumours that these individuals were not endorsed by the former guerrillas, and that this is due to the alleged interest of a family in owning land in the municipality: the Pulecio family, about which little information is available in the region. Those who dare to speak out, claim that they, the Pulecio family, have satellite internet in Tierra Linda and drive around the trails in flashy pick-up trucks.

“They cut down at least 2,350 hectares in less than three years, and it is now much larger. If you consider that one hectare can only hold two cattle to feed on good grass, and these people can raise between 1,500 and 2,000 steers per year! So, imagine how much land these people have… and how much money they have “, claims a leader that spoke to this portal, who prefers to remain anonymous because he believes discussing this family could jeopardize his safety.

The communities also blame two agricultural and veterinary product traders. They are Mario Tejada, owner of Proveedora Tierras y Ganado, and José Alirio Barreto Yanten, owner of Campolider S A S, both of which are in Cartagena del Chaira’s town centre. They are being investigated for, allegedly, deforesting a large area of forest in order to build extensive cattle ranches in the Barcelona neighbourhood of Nucleus 15.

VerdadAbierta.com tracked down both businessmen using phone numbers found in Florencia’s Chamber of Commerce records. The person who answered the phone for Tejada’s company was evasive with answers about his alleged role in Amazon deforestation, and communication on Barreto’s numbers was impossible.

According to regional leaders, in 2018, at a meeting in Remolinos del Caguán that brought together several core coordinators from all over the municipality and in which several state entities, including Corpoamazona, participated, the spokespersons of the communities denounced the people who were deforesting the forest with their own names and ID numbers, but nothing happened and, on the contrary, the denouncers made new enemies.

“The government institutions never say anything to these people; it’s the poor people who are being set up,” they say within their own communities.

Furthermore, a list of social leaders was circulated in Cartagena del Chairá weeks after that meeting, whom FARC dissidents declared a “military objective.” It was later revealed that those threatened were simply doing their socio-environmental work. But the fear is anything but dormant.

Municipal leaders agree that most landowners in the Middle and Lower Caguán live outside the region and have stewards or peasant partners working the farms. They visit the farms on occasion, but they quickly leave.

Livestock interests

Large tracts of the jungle must be deforested, which costs a lot of money. According to the quick calculations of a Bajo Caguán social leader who preferred anonymity for security reasons, he stated that “a hectare of clearing is worth around one million pesos because you will not be able to clear it yourself: the food, the tools, the gasoline, everything! Those who clear more than five hectares are those who assist them… who pay them.”

Emilio Rodriguez, a researcher at the Foundation for Conservation and Sustainable Development (FCDS), believes cattle ranchers from all over the country are sending cattle to the south, specifically Medio and Bajo Caguán, to fatten them up and then sell them at a profit. Several leaders agree that they are from Cundinamarca, Antioquia, Huila, and, most notably, Valle del Cauca.

Farmers in the area explain how the business works: one farmer pays for the deforestation, another fixes pastures, and a third brings in the cattle. They leave one or two cattle per hectare for two to three years, then sell each head of cattle for $2.5 million and split the profits.

“The big deforesters find cover within the small ones, and that’s what they’re doing to us,” a farmer from the Las Quillas area complains. Another peasant farmer in this community gives the following example of a family with a few cattle: “Consider Las Quillas, where the most trees that were chopped were over a three-hectare area. Unfortunately, we are a herd of poor people in this village “, and he also specifies that in this community of 18 families, the family with the most cattle has around 30, and the family with the most deforestation has chopped arounds three hectares at the start of this year.

Even though cattle production is currently a major concern, livestock farming did not appear in the municipality following the departure of the former FARC. According to a legend, it was the state itself that promoted and encouraged this economic activity among war victims.

The communities refer to the displacements experienced by residents of Bajo Caguán during the years of Plan Patriota – the military strategy implemented during then-President Alvaro Uribe’s first term in office (2002-2006 and 2006-2010), which sought to reclaim territories previously dominated by the FARC. When it reopened in the mid-2000s, the Agrarian Bank made loans to the Solidarity Economy Association of the Middle and Lower Caguán (ASOES) to promote livestock farming.

“For the first loan, the Agrarian Bank lent more than $1.2 billion, giving each farmer six million pesos in cattle. The farmers then began to deforest the mountains in order to make room for the cattle. A farmer with one hectare of coca mountain could subsist on that. On the other hand, if he wanted to live off cattle, he required large extensions of the mountain to make a living from milk and cheese “, says a regional leader who has lived in the Bajo Caguán region for over 20 years.

The communities recall that, by 2015, the national government focused on the beginnings of deforestation, but the real ravages of forest clearance came in 2017 when people became convinced that cattle ranching would be the activity that would legally generate money.

“By 2017 and 2018, there was evidence that there was a large capital financing peasants to clear forest. During that period, it was clear that there was a capital of dubious origin, deriving from landowners, including people from Medellín and other parts of the country, who realized that this area was good to cut down, plant pastures, and get the cattle out quickly,” the leader claims.

Statistics back up what the leader previously stated. Caquetá has seen a steady increase in cattle and cattle farms. According to the Colombian Agricultural Institute (ICA), there was 1,340,049 heads of cattle and 13,263 cattle farms in Caquetá in 2016. By 2021, there would be 2,079,194 cattle and 19,000 farms registered. This translates to a 55% increase in cattle heads and a 43% increase in cattle holdings over the course of five years.

By 2021, Cartagena del Chairá had risen to a second place in the department for the number of animals and land dedicated to livestock farming, only after San Vicente del Caguán. According to the ICA, 307,415 cattle and 2,047 cattle farms were registered, representing an increase of 137% and 84%, respectively, over 2016 records.

Leadership, under risk

“The dissidents arrived two years after the Peace Accord’s signing to control the area but there was nothing left to control,” explains a regional leader who prefers to remain anonymous. He specifies that the illegal armed group has instructed him that 30% of the land they take can be used for production, 10% for rotation, and the remaining 60% for conservation.

“They, the FARC dissidents, say, ‘We can’t stop people from coming into work because we are also peasants,’ but they don’t impose themselves in that regard. They do impose themselves, however, on the case of bringing people from other parts of the country to work in this region. There is no problem for them if it is people who are going to work there “, claims another leader with a long history in the Bajo Caguán region.

Those interviewed take varying positions on the role of FARC dissidents in deforestation. Some contradict the claims that they remain on the sidelines or that they are interested in environmental conservation. “They help to fund deforestation and encourage people to plant coca. A farmer arrives and says, ‘Let me cut 100 hectares, I’ll give you a certain amount’”, says a farmer who prefers to remain anonymous for security reasons.

These versions of the dissidents’ interests are acknowledged by an official of a state institution who requested that his name and that of the organization be kept confidential due to his position: “There is no defining line. Some allow it, while others do not. It’s not so much of where they allow it as much as where they don’t allow it. Where it is not permitted is closer to where the new Segunda Marquetalia structures are, in San Vicente Alto, high in the mountain range. Regarding the Front 1 dissidents, we see that, though not as clearly, they benefit from deforestation because they tell people to “sow and cultivate such and such, or they allow others to carry out these deforestations. This type of deforestation would not occur if they were protected.”

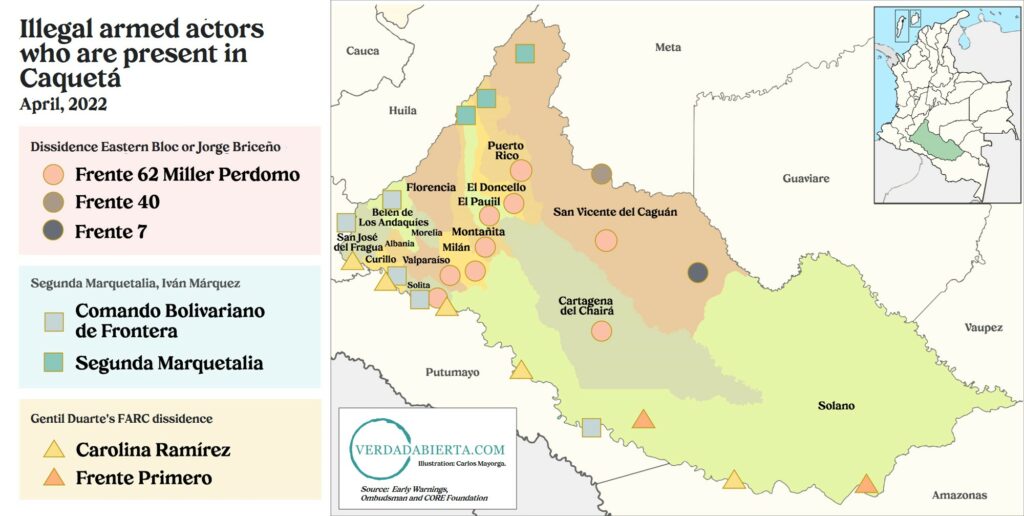

Between 2016 and 2017, the communities of Middle and Lower Caguán coexisted with irregular armed forces groups, although it is unclear whether they were from the former FARC or third parties who took advantage of the lack of authority at the time. During those years, the dissidents of Fronts 1 and 7 began to occupy the Caqueta jungle between the Guayas and Caguán rivers, with influence in Puerto Rico, San Vicente del Caguán, and Cartagena del Chairá.

The Miller Perdomo Front, a dissident structure of the former FARC’s Eastern Bloc, initially led by Édgar Mesas Salgado Aragón, alias ‘Rodrigo Cadete,’ who was at the helm of this illegal armed group until his death in February 2019 during a military operation, burst onto the scene in this context. He is credited with combating common crime while posing as a member of the FARC and uniting the presence of dissidents in that Amazon region.

Following the death of alias ‘Cadete,’ several former guerrillas assumed command of the Miller Perdomo Front, with some meeting the same fate as their predecessor or, on the contrary, being captured. Germán Amado Porras, alias ‘Cipriano González,’ a seasoned 40th Front fighter in charge of the former FARC’s training schools, was killed by army troops on August 17, last year.

Since that time, community leaders have been unsure of whom the dissident leader in charge of the Miller Perdomo Front is, causing confusion and insecurity regarding the limits of said leadership. “The dissidents, unlike the true FARC, do not have a clear north. That is why we have found ourselves between a rock and a hard place. The path to becoming a leader has become more difficult “concludes a regional leader who prefers to remain anonymous for security reasons.

Even though this dissident front is one of the most powerful in Bajo Caguán, tensions remain in the lower Caquetá River region with a group known as the Bolivarian Border Command, which in February 2021 allied with the so-called Second Marquetalia, led by ‘Iván Márquez,’ who was against the Peace Agreement despite being a member of the negotiating team and, ultimately, took up arms again.

Counting falling trees

According to Yolanda González Hernández, director-general of the Institute of Hydrology, Meteorology, and Environmental Studies (IDEAM), natural forests cover 71% of the department of Caquetá’s surface area, “with nearly 6.4 million hectares of forest, representing 16% of the forest area of the Colombian Amazon and 11% of the country’s total forest.”

This institution’s deforestation monitoring has not yet finished consolidating last year’s figures, and it’s not even possible to consult the last two Early Deforestation Detection bulletins (n° 28 and 29 respectively) on the situation in the second half of 2021 because, according to the press office, they are still being designed and published.

The most recent data on the impact of deforestation is from 2020. In that year, the Caquetá department recorded 32,522 hectares of deforestation, representing a 7% increase in IDEAM data compared to 2019, when deforestation was recorded at 30,317 hectares.

“For the last four years, from 2017 to 2020, a consolidated area of 169,904 hectares was identified for the jurisdiction of the department of Caquetá, with 2017 being the year with the most deforestation, with 60,301 hectares,” González says. This means that Caquetá, an area larger than the Hong Kong Island in China, has been deforested in four years.

During this period, the Caqueta municipalities that have accumulated the largest deforested areas are San Vicente del Caguán (72,092 hectares); Cartagena del Chairá (65,749 hectares); and Solano (22,107 hectares). However, if the total area of the municipalities is considered, Cartagena del Chairá is the most deforested region in percentage terms, losing the equivalent of almost 526,000 Olympic swimming pools in virgin forests.

According to the Sinchi Institute through the Territorial Information System of the Colombian Amazon (SIAT-AC), the two municipalities with the highest indexes of hot spots – thermal variations in the land surface that can resemble fires – were San Vicente del Caguán (49,613) and Cartagena del Chairá (32,587).

According to this data, the year with the highest recorded hot spots in Cartagena del Chairá occurred this year. So far in 2022, the SIAT-AC recorded 10,903 hot spots in the municipality, double the records of 2020, the second highest.

VerdadAbierta.com sought an interview with Corpoamazonía officials to get their analysis of what is happening in Cartagena del Chairá, but although they were given a guide of questions, they delayed their response because they are waiting for the deforestation figures from IDEAM to “provide accurate data”.

Prosecute action against deforestation

With Ruling STC 4360 DE 2018, the result of a guardianship action filed by 25 children and young teens around the country, the Supreme Court of Justice protected the rights of the Colombian Amazon, ordering the State to formulate a short, medium and long-term action plan to counteract the rate of deforestation.

Leaders of Cartagena del Chairá and neighbouring municipalities consider that this plan is only seen as a military action which, in practice, has no effective control over the territory, due to the fact that, although the National Navy verifies and photographs identity cards and registers the belongings of all those who navigate the Caguán river at different points, no military presence is present on the trail that goes from Remolinos del Caguán to the town centre of the municipality.

“We thought that the operations were against people who were inside the National Parks because there were people who had their cattle taken away, captured and taken away,” says a leader from the region who asked for his name to be withheld, and continues: “But at the end of 2020, Operation Artemisa is coming to Cartagena del Chairá after the areas of Law 2 of 1959, the Forest Reserve Zones”.

The first operation took place on October 11, 2020. On that occasion, the 17th Prosecutor’s Office of the Specialised Directorate against Human Rights Violations in Medellín requested 16 raids in the municipalities of San Vicente del Caguán and Cartagena del Chairá and arrested nine people, accusing them of the crimes of invasion of Areas of Special Ecological Importance, illegal exploitation of renewable natural resources and arson. They were released the following day.

During one of the raids Isaac Páez was captured, a farmer who for several years lived on a 170-hectare farm in the village of Lejanías in nucleus 14, but had sold it in 2018 to move to the town centre of the municipality.

On October 29 of the same month, another operation took place in Cartagena del Chairá, but this time only Páez was captured. He was again released the following day. “The judge decided to release us because the evidence he had was not conclusive, the only fact was that we were living in a Law 2 zone,” said Páez.

The journalistic programme Direct Witness in its November 30 broadcast entitled: Dissidents and drug traffickers: a perverse alliance against the Colombian Amazon presented an organisation chart that included a photo of Páez with the alias of ‘Misingo’ and linked him as the right-hand man of ‘Gentil Duarte’ in the deforestation of the south of the department of Meta. He based this accusation on information provided by the Environmental Security Headquarters of the Carabineros Police, headed by Colonel Óscar Daza. “This photo was taken on October 10, when I was captured in the Larandia installations”, says Páez in an official document which he sent to the Caquetá Ombudsman office.

“Plan Artemisa is for the poor,” reproaches another leader of the municipality. “Plan Artemisa is a persecution of the poor and of the ordinary peasants. The arrests that were made were of poor people who are struggling to have a better future for their children. But if you look at the people who have two or three thousand hectares, Plan Artemisa has not touched them at all”.

At the beginning of December, last year, several media outlets published the faces of eight men and one woman, presented as “the most wanted for deforestation in the Colombian Amazon”. The Ministry of Defence offered a reward of 20 million dollars for information leading to their capture. Again, peasants in Caquetá denounced that an error had been made in this information.

This is the case of Esteban Cruz Chilo. The local media “Lente Regional” raised the complaint of his family, who argued that he was a poor and elderly peasant farmer from San Vicente del Caguán.

Two months later, three of those named were arrested and in April of the same year four more turned themselves in. One of them was Cruz, who denounced that the whole thing was a set-up. He explained that he turned himself in not because he was guilty, but to avoid further damage to his integrity.

Cayeron 3 del cartel de los más buscados por la deforestación de la Amazonía Colombiana https://t.co/eZB1p7JvDD pic.twitter.com/ehEXNOcGld

— Mindefensa (@mindefensa) February 21, 2021

In the new “cartel of deforesters” that the Ministry of Defence disseminated through its social networks in February last year, it placed at the top of their list Jaiber Galindo Muñoz, a 45-year-old professional born into a peasant family in Saladoblanco, Huila, who was taken to live in Cartagena del Chairá at a very young age. Although he graduated as a psychologist, he never left the municipality of Caqueteño, where he is an outstanding social leader.

In 2007, he and his wife bought a farm in Los Andaquíes, a hamlet in Nucleus 15, which they deeded and on which they pay taxes. “I am one of the people who has deforested the least, anyone can see that,” says Galindo, who has insisted on putting a stop to deforestation for the past five years.

With the departure of the FARC, this psychologist became concerned about the hundreds of families who came to take over the nation’s wastelands that were part of the Amazon Forest Reserve Zone.

“Most of them were peasants,” the leader recalls, “90% of them were people who had never had the opportunity to own land. They started in a totally disorderly way: knockdown, damage, take and sell. As I was involved in several community processes, many people asked me what we could do to stop this issue of wastelands from continuing. So, we called people together and created an association.”

This is the Peasant Association for Environmental Protection and Agroforestry Production of Cartagena del Chairá (ASOPROACAR) – which Isaac Páez also supported – this association brought together 14 Juntas de Acción Comunal that were created in the areas that the families had taken over and which bordered nuclei 4, 5, 7 and 15 – encompassing the entire region from the Monterrey hamlet to the mouth of the Lobos outflow in the Yarí river.

Galindo took on the task of teaching people how to reduce deforestation, but paradoxically, this role put him in the institutional spotlight. However, it was not the first time he had been recognised for his activism in the region.

In 2015, Galindo and Páez denounced the current mayor of Cartagena del Chairá, Edilberto Molina Hernández, who by that year was the manager of Gendecar S.A.E.S.P., a company that managed the public lighting service in the non-interconnected hamlets of Cartagena del Chairá, Solano and San Vicente del Caguán.

Galindo complained that despite the company receiving subsidies from the Ministry of Mines and Energy to provide electricity to vulnerable communities, the service was not provided in at least 12 villages.

In 2017, the Superintendency of Household Public Utilities issued an indictment against Gendecar for submitting inaccurate information on the provision of electricity services between October 2014 and December 2016 in San Vicente del Caguán and Cartagena del Chairá. Although the Public Prosecutors Office found the company responsible, to date the process is still active and there is no final judgement.

“Together with Jesús Narváez – another one of those who appear on the police poster – we got a lawyer and we presented ourselves on July 7 last year and there we agreed with the Cartagena del Chairá Prosecutor’s Office, through what is known as a principle of opportunity, to avoid prosecution, that we would give some training motivating people, not to deforest and that we would plant some trees. That would practically end the process”, explains Galindo, who is awaiting a hearing to finalise the issue “and define how many trees we have to plant and how many talks we have to give”, a mechanism, he adds, that will prevent him from ending up in a trial in which he fears that false evidence will be presented against him.

Like Galindo’s situation, there are other cases involving at least 22 peasants accused of deforestation – at least eight from Cartagena del Chaira. Some were arrested, others voluntarily presented themselves to the Public Prosecutors Office and were released on the condition that they could not return to the rural properties where they lived. However, as they have no other place to live, they remain on their farms in fear that the state will come after them.

Earlier this year, the Ministry of Defence released a new poster with the details of 17 people accused of deforestation in the Amazon. Leaders consulted in Cartagena del Chairá do not know how many of them are from this municipality, but there are doubts that they are the real predators of the forest.

El ministro @Diego_Molano presentó el cartel de los 17 más buscados por delitos ambientales y deforestación, y ofreció un plan de recompensas de hasta de $300 millones a quienes suministren información que permita la ubicación y captura de los responsables por estos delitos pic.twitter.com/gMi3el4THU

— Mindefensa (@mindefensa) February 5, 2022

In order to find out more details, VerdadAbierta.com sent a right of petition to the General Command of the Military Forces requesting information on the number of captures, seizures, educational actions and the budget allocated to tackle deforestation.

More than two months later, General Jorge León González Parra, head of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, refused to respond on the grounds that he had to know “at least the objective and the reasons on which the request is based”, even though it was made clear that the information requested was related to a journalistic investigation.

When the query was escalated, the Ministry of Defence transferred the responsibility of responding to this portal to the Caquetá Police Department. This institution stated that between December 13, 2017 – the date on which the environmental bubble was declared – and February 10, 2022, 259 arrests were made in this department for crimes against natural resources and the environment in areas of Forest Reserves and National Natural Parks.

In the specific case of Cartagena del Chairá, he indicated that eight people were arrested during this period, one of whom was arrested in 2020 for illegal exploitation of renewable natural resources and four more for invasion of areas of special ecological importance.

For its part, the Attorney General’s Office said that in Cartagena del Chairá, between December 13, 2017 and March 3 this year, three people have been charged with crimes related to deforestation, two of which have reached the trial stage.

This portal asked the investigating body how many cases that went to trial in Caquetá were resolved by convictions and acquittals, but the enquiry was passed on to the Superior Council of the Judiciary and at the time of going to press there had been no response.

Mobilisations against judicialization

The judicialization in 2020 provoked a social explosion in Cartagena del Chairá. On November 13 of that year, in the middle of the pandemic, amidst masks and bottles of antiseptic alcohol, more than 300 people mobilised towards the municipal capital, seeking to make their disagreement heard about the methods used to stop deforestation: the arrests.

“We did a peaceful demonstration simply with banners saying that we were not criminals, that we were working peasants and that the Prosecutor’s Office is not aware of the worst killers of the environment”, recalls a leader from the region.

As a result of this protest, the Municipal Roundtable of Agro-environmental Farmers’ Consultation for the Right to Land was formed, a social process in Cartagena del Chairá that seeks to propose solutions to deforestation and the land tenure situation of hundreds of families in the municipality.

The peasant communities demanded that the national government cease all judicial persecution and proposed that the areas of the forest reserve that are already occupied by families be subtracted from the reserve and that these areas enter the national land bank to be assigned to the same families that occupy them.

They also complained to the Executive branch that the failure to comply with point one of the Peace Accord, Integral Rural Reform, had catapulted families onto land in the department and that international cooperation money for Amazonian conservation had been used only for military action.

However, the operations did not cease. On April 15 last year, more than 600 peasants mobilised from Cartagena del Chairá to Florencia to reiterate their demands, forming a group of 2,800 peasants from all over Caquetá. And they joined the National Strike, setting up “resistance points” in three municipalities in the department of Huila: Altamira, Guadalupe and Suaza, where they managed to get various state bodies to sit down and listen to them and look for solutions.

One of the points addressed the situation of families settled in forest reserve zones, which agreed to the financing of two subtraction studies in San Vicente del Caguán and one in Cartagena del Chairá, adding also access to credit and agricultural extension for peasant communities, and the financing of four participatory environmental zonings in the department. However, to date, the only point on which progress has been made is in participatory environmental zoning, through community assemblies.

The proposals of the leaders of Cartagena del Chairá are aimed at achieving the permanence of the communities in the territory, as they consider that at this point it is already very difficult to remove and relocate the families who in recent years have taken over part of the forest, and even more so those who have lived in this part of the country for more than 40 years. That is why their struggle is to obtain Forest Reserve Zones with peasants.

One of the proposals is to implement a “model farm” where the food security of the families is guaranteed, agricultural production is guaranteed and the offers of payments for environmental services are linked to the conservation of the forest.

“These peasants have to be taught to protect themselves, but they are there because they need to make a living with their wives and children. They should tell the peasant farmer ‘in this territory the only thing you can do is this and this’ and that they should give them the aid and inputs to conserve themselves”, reiterates one of the leaders consulted.

Wait for our next instalment: VerdadAbierta.com asked about the actions being taken by peasant farmers in Cartagena del Chairá to counteract deforestation and make life viable in Bajo Caguán. He also reviewed the progress of the National Conservation Contracts and Payments for Environmental Services offered by the government as a solution for the special management zones.

This article was made possible thanks to the support of Environment and Society Association, and the support provided by the Municipal Agro-environmental Roundtable for the Right to Land of Cartagena del Chairá, Caquetá.